Review: Breakfast at Tiffany's by Truman Capote

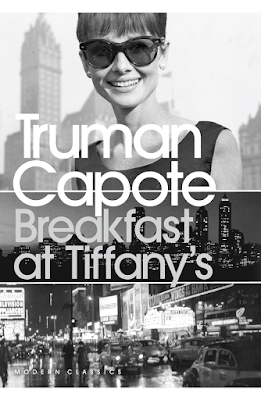

Audrey Hepburn in that dress as the gorgeously elegant Holly Golightly, is one of the most iconic images of twentieth century Hollywood. But Truman Capote’s novella is some way removed from the sweet romance of the 1961 film adaptation of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Lacking none of the glamour, Capote weaves the painful lightness of Holly Golightly’s life in Manhattan with far darker and more interesting themes in his slim novella and disposes of the happy ending that a big screen picture demands.

Capote’s 1958 novella is narrated by an unnamed author who recounts the small amount of time he spent living in the same block as nineteen-year-old Holly Golightly, a young actress turned society girl who hosts parties in her small apartment as well as receiving a string of wealthy if rather unappealing men, mostly tipping middle-age. Miss Golightly’s past is a mystery to the narrator, who she names Fred in reference to her brother who she left in her old life, wherever and whatever that might be. Fred, as I might as well call the narrator for the sake of convenience, is one in a long line of men, and probably women, to be infatuated with Holly (not necessarily sexually, but attracted to her energy, the essence of her existence). Whether or not she is a “phony”, as one of her male visitors claims, is immaterial, she, existing as cotton upon the wind, is captivating to readers and fellow characters alike and as the meagre plot runs out, it is the experience of being in Miss Golightly’s company that keeps the pages turning more than the story that she inhabits.

Framing Holly’s story within Fred’s narrative is a clever trick. Like Nick Carraway’s recounting of his time with Jay Gatsby, the narrator looks on with jaw slightly agape at a character who possess a life force far exceeding their own. Fred’s relating of the brief time that his life rubbed up against the vivacity of his glamourous neighbour cannot be the first or last time a man has sat in a bar telling stories of the enigmatic Miss Golightly, a spectre who had passed through their life and then disappeared into the unknown world. As with Carraway’s ambiguous idolisation of Gatsby, it is far easier to be swept up in the romance of a character when their story is told by another who observes only that which sparkles about their adored protagonist.

But like Gatsby, there is much to Holly that is hidden beneath the surface of her lifestyle. Indeed, the more Fred learns of Holly and her past, the more he sees not a sophisticated young woman who is in control of her own destiny but rather a girl who is hiding in plain sight, hoping that eventually the glare from all that shines around her will be blinding enough to completely obscure her past. This is one of the elements the film gets right. The iconic image of Audrey Hepburn peering into the window of Tiffany’s in the film adaptation is a perfect portrait of a soul gazing in at the world of decadence and wishing desperately that all the fine things she might one day accrue will be the ultimate palliative for real life. In this way, Holly is a perfect analogy for the dangers of consumerism – she sells her body to rich men (commodifying herself) in order to acquire (consume) material things that she hopes will heal her troubled soul. In other words, she is a capitalist’s wet dream.

On that note, it is perhaps the opportune moment to raise the issue of Marilyn Monroe, blonde icon from the era, friend of Truman Capote, and with whom Holly has a fair amount in common. In fact, if Capote is to be believed (as with most of his stories there is every reason to be cautious here), he would have had Marilyn play the role in the film adaptation ahead of Audrey Hepburn. It would certainly have given the film a different feel and when one considers Monroe’s early biography – an orphan who was shunted around and would experience sexual assaults before eventually marrying an older man (he was 21 when she was 16) in a bid to escape her life but whom she would later divorce – it is not difficult to see parallels between the two women. Indeed, the air that Monroe had, of her vivacity covering a deeper pathos would have been far closer to the book’s Holly than Audrey Hepburn’s assured and naturally elegant poise.

As with this duality in Holly’s personality – the darkness hidden beneath all that shimmers – much of the novella is concerned with the masks which we use to disguise reality and which help us to form in our own minds a world that we find acceptable. When her agent describes Holly as a “real phony” the phrase seems less a contradiction in terms and more a compliment to the openness of Holly’s approach to life: for though she hides her past, she makes no attempt to disguise the reckless frivolity of her life or the transient nature of all her whims and pleasures. She may be a “phony” but she’s not hiding it from anyone.

Interestingly, Holly sees something of herself in Fred. When she describes him thus she could be talking about herself: "He wants awfully to be on the inside staring out: anybody with their nose pressed against the glass is liable to look stupid." The irony, of course, is that Holly herself is a perpetual outsider, never allowing anyone to get close enough to form an in-group with her. As the nameplate on her mailbox alludes (“Miss Holly Golightly, travelling”), for the young socialite, connections are fleeting. For indeed, Holly does go lightly, her ephemeral presence brushing softly against the world like a feather across satin. This only goes to highlight the importance of connection to people and place, both of which Holly lacks and which leave her adrift in a world where many seek her but few want her long-term.

This is where Holly’s character becomes interesting and impenetrable in equal measure. Tiffany’s represents the elegance and permanence that Holly aspires to in her own life but while she is enraptured by the capitalist dream of luxury and a well-to-do family she also carries a great desire for freedom, for living outside of social convention. She hates cages of all kinds and has wrought for herself a life that does not constrain but that leaves her free to roam as the “wild thing” she is. This paradox is a tragic mix and one that no doubt contributes to her depressive episodes (her “deep reds” as she refers to them).

Undoubtedly, Capote’s excellent drawing of Holly Golightly is what sells the story; the plot is slim at best. But how beautifully Capote details his characters and their story. He writes exquisite prose, less ornate than Fitzgerald but as carefully crafted and full of small observations:

“We giggled, ran, sang along the paths toward the old wooden boathouse, now gone. Leaves floated on the lake; on the shore, a park-man was fanning a bonfire of them, and the smoke, rising like Indian signals, was the only smudge on the quivering air. I thought of the future, and spoke of the past.”

In a novella where words are limited it is all the more obvious when an author has honed his thoughts into their perfect form. Like finely cut diamonds, Capote’s sentences shimmer with carefully worked beauty that has been buffed to perfection. References to Fitzgerald, however, are more relevant than simply as a comparison for sharp prose – structurally Breakfast at Tiffany’s is remarkably similar to The Great Gatsby and it seems almost impossible that Capote did not have Fitzgerald’s exquisite gem to hand when he was crafting his own. Compare the closing line from The Great Gatsby below with the opening line from Breakfast at Tiffany’s below:

Gatsby: "So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

Breakfast at Tiffany’s: "I am always drawn back to places where I have lived, the houses and their neighbourhoods."

It is as though one story picks up where the other left off, looking back, always back, as the future “recedes before us.”

Breakfast at Tiffany’s aches with the sure knowledge that we belong to one another and that, through stories and experiences, every life is made unique through those who gaze upon it. Holly may not quite appreciate this fact as she lives her life of nomadic transience but she will, undoubtedly, one day come to appreciate the full spectrum of what she has left behind and long for missed opportunities and connections cut short too early. Breakfast at Tiffany’s is a novella that evokes all those beautifully painful emotions associated with nostalgia and the thought of people who, having crossed one’s path, disappear into the world never to be seen again. It is a novella that more than matches its big screen adaptation and can be read in little more than the film’s run time. A small mid-twentieth century gem.

1 Comments

Very good write-up. I absolutely love this website.

ReplyDeleteStick with it!

I always welcome comments...