Review: Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore by Robin Sloan

If you want to sell books to book people, write a book about books. Why not throw in an ancient mystery that is solved through a series of mini-quests and add more than a dash of techno-babble too, to keep things fresh? The resulting book sells itself, well, with the help of a few choices quotes from the likes of Erin Morgenstern on the cover (a sure sign for caution in my experience). It is, as they say, ‘a banker’. Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore (2012) is certainly that – a book that sounds great in elevator pitch form, so let me give you the sell:

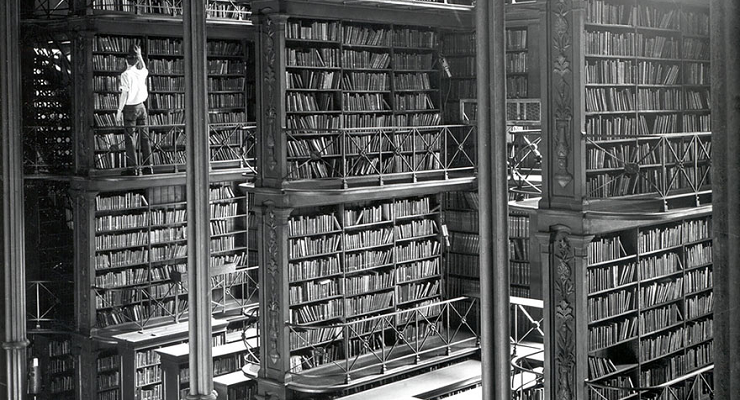

Clay Jannon is a would-be graphic designer who, having lost his job at a San Franciscan start-up, is on the lookout for a new position. This leads him to Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore. Tucked inconspicuously in beside a strip club, the mysterious bookshop is remarkably narrow but has bookshelves that stretch high up above ground level. Clay acquires the role of night-clerk, looking after the odd assortment of books – those from the ‘wayback’ collection are written in an indecipherable code – during sleeping hours. If the books are an odd assortment of arcane codices, then the small number of customers that frequent the bookshop are even more peculiar. There are clearly mysteries to be solved and with the help of Googler and love interest Kat Potente, Clay is, in pursuit of answers, pulled into the path of a centuries’ old cult called ‘The Unbroken Spine’, who also seek to solve the riddle of Gerritszoon, a sixteenth century typographer whose coded message, they believe, holds the key to eternal youth. It is a tall order and Clay will need to call on all his resources and Silicon Valley friends to get to the bottom of this bibliophilic mystery.

To borrow a line from the novel itself, Mr Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore is undoubtedly a book that exists at the intersection where technology and books meet. From the sales blurb, it might be a surprise to some readers to find that there is at least as much about new technologies in the story as there is about books and ancient mysteries. Indeed, if a novel has ever included the word Google as frequently, I would be surprised. This dialectic between old and new is important to the novel, however. With a centuries’ old mystery to solve, there is an interesting discussion to be had about the ways in which technology now allows information to be recorded and manipulated like never before, and whether the superior processing power of computers can extend beyond solving logical problems and unravel different forms of information.

At the heart of the novel is another rather interesting discussion that permeates our digital world: when you duplicate content, is the result a copy or simply a replica? It is a question that should send our minds back a couple of millennia to Plato’s cave but it is increasingly relevant today. In Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, characters are largely split down the two sides of the argument – those who believe there is something ineffably unique about real items you can touch and which are original, and those who believe an object’s value is in its meaning, its data. Thus, if you can extract content from form do you lose something or do you gain the ability to manipulate the content more effectively? It is a discussion that has pretty big implications for the reality we are constructing for ourselves but whether Sloan’s novel quite gets to the heart of the matter is debatable. It is clear that Clay himself is torn between the two schools of thought – although he utilises computer modelling to uncover the secrets Mr. Penumbra’s bookstore holds, he also appreciates the more romantic appeal of books: “Walking the stacks in a library, dragging your fingers across the spines - it's hard not to feel the presence of sleeping spirits.”

The digital terrain that Sloan walks clearly puts him in Coupland territory and there are undoubtedly similarities between the styles of both authors. Most notably, the way in which their writing is so immersed in the current age that technology metaphors and analogies abound at the turn of every page. Take, for example, this rather nice example where Sloan uses a common digital idea to describe an emotion: “He has the strangest expression on his face - the emotional equivalent of 404 PAGE NOT FOUND.” This interlocking of technology and humanity is nicely done and permeates down to the deepest levels of the text.

The keen eyed reader will also notice that there are endless references to talented people of the past – both overt and subtle – and this helps situate the story in its historical context. However, while it feels like one is being exposed to interesting facts about the history of typography and bookmaking, and the more modern world of Google, it is slightly disappointing to find that when one scratches beneath the surface many of the facts in the novel are distortions of reality and less educative than one might imagine on first glance. These are nice touches though, and help maintain interest.

That said, Sloan manages to keep the momentum of the story going. Although one suspects that the revelation, when it comes, will be a let-down and Clay and his assorted chums will navigate the plot successfully, there are still enough interesting tit bits and small intrigues to keep things interesting. Readers – nay, humans – are very easily manipulated and at the merest hint of a mystery we are willing to invest a disproportionate amount of effort into discovering the revelatory answer (as demonstrated by all those painfully transparent link-bait articles that are headlined things like ‘You’ll never believe why Taylor Swift was thrown out of this club’, or ‘The one secret that will help you lose ten pounds in your lunch break’). Sadly, working through Mr Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore comes with a similar feeling of shame at your blatant manipulation as when you click on one of those link-bait articles to allow you to sate the curiosity that has been stoked only seconds before.

In total, the novel is a bit of a mixed bag. It started life as a short story that Sloan put out as an e-only release a year before Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore hit the shelves and I am tempted to suggest it perhaps should have remained in its shorter form. It can be difficult to build a story strong enough to support a good initial idea. As noted in the book itself, “Imagination runs out. But it makes sense, right? We probably just imagine things based on what we already know, and we run out of analogies in the thirty-first century.” Perhaps Sloan’s imagination ran a little short of developing a plot to match the interesting ideas around Penumbra’s bookstore and The Unbroken Spine. The resulting story is a mix of good ideas and fairly formulaic execution. A bit of fun but not wholly satisfying.

0 Comments

I always welcome comments...