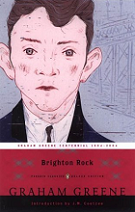

Review: Brighton Rock by Graham Greene

Brighton Rock (1938) is one of Graham Greene’s most famous works, and one of his ‘Catholic novels’. Kolley Kibber, or Fred, is a newspaper man visiting Brighton for work. Later known by his real name, Hale, he has fallen in with the wrong crowd, and a quiet day by the sea soon turns into a race against death as a local gang pursue him. Latching on to a buxom, good-time girl down from London, Hale hopes to escape the gang’s clutches. But Ida Arnold cannot save him, and soon the gang catch up with Hale. Pinkie, a scrawny but sociopathically cold seventeen-year-old, is the (ironically) Bonapartean leader of the gang, and he doesn’t flinch as his crew murder Hale. Ida, who, when Hale disappeared, assumed she had been passed over, only learns of his death, reported in the local news as a result of a health condition, a few days later. Knowing in her gut that things are not right, Ida sets out to uncover the truth. This spells trouble for Pinkie and to cover his tracks he must spill more blood, battle with local gangster Colleoni, and marry a sixteen-year-old waitress, Rose, to stop her testifying against him. A timid girl, Rose shows a blind faith in Pinkie, but Ida dogs the pair, struggling always to make Rose see sense and ‘save’ her.

Hale’s murder is a vengeance killing, preceded, in A Gun for Sale, by the murder of Kite, leader of Pinkie’s gang. Hale’s attempted escape from death in the opening pages of Brighton Rock sets up neatly the notion of man’s struggle with existence, the need to protect oneself in the anonymity of the world in order to sustain life. His identity shifts; he struggles half-heartedly against the inevitable.

The 1930s were a time of depression and austerity. With political ideologies taking advantage of the landscape across Europe, Greene was sceptical of inflexible doctrine, whether political or religious. He grappled often with the big questions, and his view that the religious could often be guilty of the worst sins, and that redemption is available in many forms, set him apart from many ‘Catholic’ writers. His characters in Brighton Rock all exist in an uncomfortable place between belief and unbelief; Pinkie believes in Hell but not Heaven, Ida has her superstitions, and Rose puts her faith in Pinkie with an almost religious fervour. All struggle with the modern world in their own way, none having found the perfect response to it. The paradoxes and dualities of his characters often represent Greene’s own disharmonious views, and those of society as a whole. This metaphysical angst is central to Brighton Rock.

However, the characters are all fairly limited in scope, Greene moulding them to represent certain values rather than to be fully-rounded persons – he is far more interested in how their positions conflict than their full psychological make-up. At times this can make the characters’ actions hard for the reader to comprehend, but there is still some essential truth in them which makes them work, if not as fully-rounded characters, then as aspects of character.

Sexually frustrated and riddled with guilt and disgust at the sexual act, Pinkie is wracked with an angst that only the religious can know. He is a cold and calculating sociopath, but he is not beyond redemption, or so Rose would have it. She is drawn to Pinkie’s nihilism, as some are drawn to the moral absolutism of Catholicism; the certainty, even of damnation, a comfort, as is the perverse need for servility and chastisement. In Rose’s case, this is rooted in her own inability to value herself. Throughout, her blind and insistent love for The Boy creates a struggle within Pinkie, he unfamiliar and uncomfortable with such unswerving affection. Pinkie’s horror at the thought of physical intimacy is related to his masculine anxiety: for all his cruel acts and power plays, he is stripped naked by the sexual act, unable to hide any flaws in his still-developing masculinity.

Pinkie’s existential angst is the most interesting element of the book, and his slow initiation into the world of affection and love, both emotional and physical is an important part of the plot. That he rejects all forms of sensuality by the novel’s close, repelled by the thought, is difficult. Ida, with her liberal attitude to sex, and full, womanly figure, represents the antithesis of Pinkie, and he finds her suitably overwhelming and distasteful. The physical appearance of the characters is important: both Pinkie and Rose are diminutive and underdeveloped, whereas Ida is full-figured, bursting with life and vitality.

Though Ida pursues Pinkie throughout, she is far from the typical detective archetype of the time: superstitious, hardly self-assured or blessed with a sharp rationality as she is. Her one immovable quality is her belief in the sanctity of life, and this is what drives her forward. Stuck between the extremes of Good and Evil that Rose and Pinkie represent, Ida is left unarmed in the middle-ground, where definites do not exist, but where one compromises for the good of man.

With their conflicting views, Pinkie and Ida each try to impress their world view upon the Rose. The young girl’s stubborn love for Pinkie is something that Ida can hardly comprehend. Undoubtedly, this is an insistent and pig-headed love, but there is the suggestion that there is a transcendent quality to it that Ida, so firmly rooted in reality, barely understands. Rose’s faith has the potential to be redemptive, and she maintains that people can change, in spite of Ida’s insistence that, like a stick of rock, people are the same all the way through. It’s a forced blindness on Rose’s part, but she is the only character who is left entirely uncriticised and so one must assume a (perceived) merit in her actions. (Greene doesn’t truly condemn Pinkie for his abhorrent behaviour either, the fallen world of his unheroic protagonist as much to blame as Pinkie himself.) Greene deals with moral ambiguity well, although the morality of the book often feels muddled or off-kilter. Why Ida is treated with disdain by the narrator is never quite clear, rational and good-spirited as she appears.

Greene’s Brighton, beyond the gawdy attractions of the front, is dank and grimy, everything depressed and decaying. Pinkie sees beyond the pomp of Brighton’s front and to the squalor behind, just as he sees beyond the physical world and into the eternal. Characters like Ida, who are firmly planted in the real world represent a turn from religion and to a man-made materialism and rationality instead. There might be a narratorial sneer reserved for these muddled characters, but in their half-thrown off superstitions they are still a step ahead of Pinkie and Rose, deluded as both are.

Pinkie and Rose’s backgrounds, each having come from the slums, shape their future, and Brighton Rock contains a social agenda buried in the metaphysical wranglings, which, on the surface, shape the novel. Ida is just one of a number of people who hound Pinkie, his life an unending chase, from which he cannot escape. From his birth he has been surrounded by decrepitude and this has birthed his dim view of the world. Pinkie is seemingly driven by his environment and yet he is still to be condemned to Hell according to Catholic doctrine, an uncomfortable truth that Greene addresses. Yet, Rose springs from the same hole as Pinkie and has none of his malice. Perhaps then, Pinkie is justly sentenced (though damnation can never be justified, really). Quite why Ida is prepared to go to such lengths to pursue justice, or at least answers, is far from clear, and this sort of contrivance is where the novel is at its thinnest. Perhaps her unwanted enquiries symbolise the secular world’s ham-fisted forays into the spiritual world, if only to condemn it, but it’s here, as they act out certain roles, that the characters lack of depth is most apparent.

Colleoni, local gangster and a man with money, who despite being far from a native of Brighton lays more claim to the place than Pinkie ever will. In the original edition of Brighton Rock, Colleoni was Jewish, but this was changed in the 1970s to make him Italian. In either case, that he is alien to Brighton emphasises Pinkie’s own slim grasp on his homeland, and acts as a shortcut to prejudices that most of the characters (and readers) would have felt towards someone like Colleoni. He represents the all-powerful owning class, outwardly respectable but with an interest in dominating and suppressing the masses. Pinkie has no chance of winning against the forces of society or Colleoni.

Greene’s writing is functional and without superfluous artistry. However, the plot is sharp, the melodramatic drama reflecting the melodrama of the pulpit. Brighton Rock is entirely free of humour and the unrelenting bleakness of the novel is indicative not only of the grim reality of slum life and religious guilt but also of the author’s own bipolar disorder.

According to Greene, Brighton Rock started life as a straight detective story. That it broadened out into something wider and more interesting surely saved it from becoming forgettable pulp fiction, and set Greene up to be an author remembered by later generations. As a historical document, the novel represents a glimpse at British life that was often glossed over at the time, and as such is valuable.

The novel is split into seven sections and, as Herbert Haber notes, in each Pinkie dishonours one of the seven sacraments. Greene believed that the moral seriousness and the gravity of consequence in a religious world where salvation and damnation existed as real (dis/)incentives, gave novels an added weight. The heaviness of theme here is in contrast to the stark style and limited characterisation. Brighton Rock is a strangely powerful and important novel, if a flawed one.

Useful Links

Reviews of Brighton Rock on Amazon (UK)

Reviews of Brighton Rock on Amazon (US)

Hale’s murder is a vengeance killing, preceded, in A Gun for Sale, by the murder of Kite, leader of Pinkie’s gang. Hale’s attempted escape from death in the opening pages of Brighton Rock sets up neatly the notion of man’s struggle with existence, the need to protect oneself in the anonymity of the world in order to sustain life. His identity shifts; he struggles half-heartedly against the inevitable.

The 1930s were a time of depression and austerity. With political ideologies taking advantage of the landscape across Europe, Greene was sceptical of inflexible doctrine, whether political or religious. He grappled often with the big questions, and his view that the religious could often be guilty of the worst sins, and that redemption is available in many forms, set him apart from many ‘Catholic’ writers. His characters in Brighton Rock all exist in an uncomfortable place between belief and unbelief; Pinkie believes in Hell but not Heaven, Ida has her superstitions, and Rose puts her faith in Pinkie with an almost religious fervour. All struggle with the modern world in their own way, none having found the perfect response to it. The paradoxes and dualities of his characters often represent Greene’s own disharmonious views, and those of society as a whole. This metaphysical angst is central to Brighton Rock.

However, the characters are all fairly limited in scope, Greene moulding them to represent certain values rather than to be fully-rounded persons – he is far more interested in how their positions conflict than their full psychological make-up. At times this can make the characters’ actions hard for the reader to comprehend, but there is still some essential truth in them which makes them work, if not as fully-rounded characters, then as aspects of character.

Sexually frustrated and riddled with guilt and disgust at the sexual act, Pinkie is wracked with an angst that only the religious can know. He is a cold and calculating sociopath, but he is not beyond redemption, or so Rose would have it. She is drawn to Pinkie’s nihilism, as some are drawn to the moral absolutism of Catholicism; the certainty, even of damnation, a comfort, as is the perverse need for servility and chastisement. In Rose’s case, this is rooted in her own inability to value herself. Throughout, her blind and insistent love for The Boy creates a struggle within Pinkie, he unfamiliar and uncomfortable with such unswerving affection. Pinkie’s horror at the thought of physical intimacy is related to his masculine anxiety: for all his cruel acts and power plays, he is stripped naked by the sexual act, unable to hide any flaws in his still-developing masculinity.

Pinkie’s existential angst is the most interesting element of the book, and his slow initiation into the world of affection and love, both emotional and physical is an important part of the plot. That he rejects all forms of sensuality by the novel’s close, repelled by the thought, is difficult. Ida, with her liberal attitude to sex, and full, womanly figure, represents the antithesis of Pinkie, and he finds her suitably overwhelming and distasteful. The physical appearance of the characters is important: both Pinkie and Rose are diminutive and underdeveloped, whereas Ida is full-figured, bursting with life and vitality.

Though Ida pursues Pinkie throughout, she is far from the typical detective archetype of the time: superstitious, hardly self-assured or blessed with a sharp rationality as she is. Her one immovable quality is her belief in the sanctity of life, and this is what drives her forward. Stuck between the extremes of Good and Evil that Rose and Pinkie represent, Ida is left unarmed in the middle-ground, where definites do not exist, but where one compromises for the good of man.

With their conflicting views, Pinkie and Ida each try to impress their world view upon the Rose. The young girl’s stubborn love for Pinkie is something that Ida can hardly comprehend. Undoubtedly, this is an insistent and pig-headed love, but there is the suggestion that there is a transcendent quality to it that Ida, so firmly rooted in reality, barely understands. Rose’s faith has the potential to be redemptive, and she maintains that people can change, in spite of Ida’s insistence that, like a stick of rock, people are the same all the way through. It’s a forced blindness on Rose’s part, but she is the only character who is left entirely uncriticised and so one must assume a (perceived) merit in her actions. (Greene doesn’t truly condemn Pinkie for his abhorrent behaviour either, the fallen world of his unheroic protagonist as much to blame as Pinkie himself.) Greene deals with moral ambiguity well, although the morality of the book often feels muddled or off-kilter. Why Ida is treated with disdain by the narrator is never quite clear, rational and good-spirited as she appears.

Greene’s Brighton, beyond the gawdy attractions of the front, is dank and grimy, everything depressed and decaying. Pinkie sees beyond the pomp of Brighton’s front and to the squalor behind, just as he sees beyond the physical world and into the eternal. Characters like Ida, who are firmly planted in the real world represent a turn from religion and to a man-made materialism and rationality instead. There might be a narratorial sneer reserved for these muddled characters, but in their half-thrown off superstitions they are still a step ahead of Pinkie and Rose, deluded as both are.

Pinkie and Rose’s backgrounds, each having come from the slums, shape their future, and Brighton Rock contains a social agenda buried in the metaphysical wranglings, which, on the surface, shape the novel. Ida is just one of a number of people who hound Pinkie, his life an unending chase, from which he cannot escape. From his birth he has been surrounded by decrepitude and this has birthed his dim view of the world. Pinkie is seemingly driven by his environment and yet he is still to be condemned to Hell according to Catholic doctrine, an uncomfortable truth that Greene addresses. Yet, Rose springs from the same hole as Pinkie and has none of his malice. Perhaps then, Pinkie is justly sentenced (though damnation can never be justified, really). Quite why Ida is prepared to go to such lengths to pursue justice, or at least answers, is far from clear, and this sort of contrivance is where the novel is at its thinnest. Perhaps her unwanted enquiries symbolise the secular world’s ham-fisted forays into the spiritual world, if only to condemn it, but it’s here, as they act out certain roles, that the characters lack of depth is most apparent.

Colleoni, local gangster and a man with money, who despite being far from a native of Brighton lays more claim to the place than Pinkie ever will. In the original edition of Brighton Rock, Colleoni was Jewish, but this was changed in the 1970s to make him Italian. In either case, that he is alien to Brighton emphasises Pinkie’s own slim grasp on his homeland, and acts as a shortcut to prejudices that most of the characters (and readers) would have felt towards someone like Colleoni. He represents the all-powerful owning class, outwardly respectable but with an interest in dominating and suppressing the masses. Pinkie has no chance of winning against the forces of society or Colleoni.

Greene’s writing is functional and without superfluous artistry. However, the plot is sharp, the melodramatic drama reflecting the melodrama of the pulpit. Brighton Rock is entirely free of humour and the unrelenting bleakness of the novel is indicative not only of the grim reality of slum life and religious guilt but also of the author’s own bipolar disorder.

According to Greene, Brighton Rock started life as a straight detective story. That it broadened out into something wider and more interesting surely saved it from becoming forgettable pulp fiction, and set Greene up to be an author remembered by later generations. As a historical document, the novel represents a glimpse at British life that was often glossed over at the time, and as such is valuable.

The novel is split into seven sections and, as Herbert Haber notes, in each Pinkie dishonours one of the seven sacraments. Greene believed that the moral seriousness and the gravity of consequence in a religious world where salvation and damnation existed as real (dis/)incentives, gave novels an added weight. The heaviness of theme here is in contrast to the stark style and limited characterisation. Brighton Rock is a strangely powerful and important novel, if a flawed one.

I don't particularly enjoy Greene's style of writing and there's quite a lot left to be desired in general about Brighton Rock, but there is something so evidently engaging about the disaffected Pinkie and his inner conflicts that I can't help but keep something of the novel with me.

Useful Links

Reviews of Brighton Rock on Amazon (UK)

Reviews of Brighton Rock on Amazon (US)

4 Comments

I think all his books are very dark and gloomy, and full of despair and decay. I've only read A Burnt Out Case and have seen The Third Man, but he's able to capture the suffering of his characters very well. Nothing I'd love to read all the time, but definitely something that leaves an impression.

ReplyDeleteIn my experience, they are. I think that is pretty much a reflection of his own mental state of mind and way of viewing the world. I can understand not wanting to spend too long dwelling on his books (although I'm clearly a gloomy soul myself, because I can tolerate it ;) )

ReplyDeleteI like gloomy (though I prefer dark) stuff. But there are different types of gloomy and Greene's gloomy is especially disturbing, so I don't like to dwell there for a long time. But it doesn't mean I don't like to return from time to time. :)

ReplyDeleteI can understand that :) Happily, I'm a gloomy bod (if that's not an oxymoron) so I'm often to be found amongst rather depressing literature.

ReplyDeleteI always welcome comments...